When an FDA ruling curbed fecal transplants, I performed my own

Susan D'Agostino UnDark

Thu, 08 Nov 2018 00:01 UTC

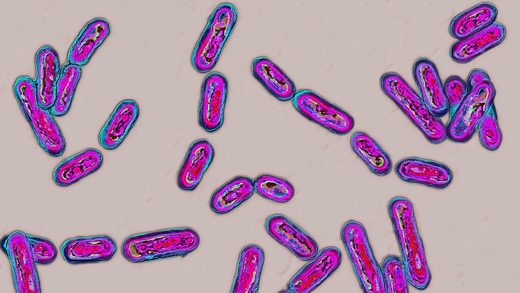

To treat stubborn gut bacterial infections caused by Clostridium difficile, some patients have performed their own fecal microbial transplants. © BSIP/UIG via Getty Images

Doctors and policymakers have been slow to endorse the treatment - a last line of defense against the superbug C. Diff. - even as many patients have embraced it.

I'd had intestinal distress before, but never like this. I was excreting not just waste, but blood and bits of my colon's lining - up to 30 times per day. My abdominal pain hit deeper and felt less productive than the pain of giving birth, epidural-free, to my second child. Even shingles, which stung like a dental drill against my face, paled in comparison. Such was the agony of Clostridium difficile.

Commonly known as C. diff., Clostridium difficile is an antibiotic-resistant superbug carried by approximately 5 percent of the adult population. The harmful gut bacterium is normally kept in check by other, good bacteria in the gut's microbiome. But when the microbial balance is upset - for example, by a dose of antibiotics - C. diff. can gain a foothold. Left to multiply unchecked, it may kill its human host.

In 2013, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimated that 14,000 Americans die each year from C. diff. Thanks to an ill-considered decision by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, and the willful ignorance of a string of doctors charged with my care, I was nearly one of them.

Things started innocently enough. In early 2013, my doctor diagnosed me with a bacterial infection and prescribed an antibiotic. I had lived antibiotic-free for nearly four decades - a streak I was not inclined to break. But my doctor insisted on antibiotics, and I reluctantly complied.

Soon after, my stomach turned against me. I went to an emergency room and was sent home with a prescription for vancomycin, an antibiotic reserved for serious bacterial infections. But the drug proved little match for the microbes that had bum-rushed my colon. My weight and fluid loss accelerated. My colon risked perforation.

Because C. diff. spores can live for months on bedrails, doorknobs, and linens and easily shrug off common detergents and sanitizers, my master bathroom became my biohazard containment unit. There, I alternated between sitting on the toilet and lying on the floor. My husband, Esteban, brought me supplies and emotional support. My two children, 9 and 11, had been instructed to stay away. I missed them.

Desperate, I looked for C. diff. cures and treatments on my phone. That's when I learned about fecalmicrobial transplants, in which stool from a healthy donor is infused into the gut of a sick patient, to restore microbial balance.

Although the procedure has only recently gained popularity in the U.S., it's been around for ages. Academics at Nanjing Medical University in China and the University of Maryland School of Medicine noted in 2012 that fecal transplants were performed in 4th century China, during the Jin dynasty. The authors wrote that the first Chinese emergency medicine book, "Zhou Hou Bei Ji Fang" (or, "Handy Therapy for Emergencies") stated that patients dying from severe diarrhea could be cured with a swallow of a human feces suspension.

Not until 1958 did the procedure appear in modern scientific literature, in the journal Surgery. Over the decades that followed, the ancient remedy repeatedly demonstrated its mettle. In 2012, Larry Brandt of New York City's Montefiore Medical Center wrote that fecal transplantation "has been shown in numerous case series to be a rapidly acting... safe... and highly effective... therapy for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection." Nine times out of 10, he found, the stool infusions vanquished even the most stubborn C. diff. infections - sometimes in a matter of hours. One research trial comparing the efficacies of fecal transplantation and vancomycin in patients with recurring C. diff. had to be stopped for ethical reasons, when it became clear that participants assigned to the fecal transplant group were recovering while those in the vancomycin group worsened.

As I learned all this from my bathroom quarantine, I was unaware that the FDA was then moving forward with a ruling that would make it nearly impossible for people like me to access the scatological remedy: The agency had decided to classify human stool as an "investigational new drug," which would effectively bring fecal transplantation to a halt in the U.S.

The FDA's rationale was thin, at best. As Brown University and MIT researchers argued in a Nature commentary, conventional drugs "are produced under controlled conditions with consistent, known ingredients. Stool is a variable, complex mixture of microbes, metabolites and human cells. It cannot be characterized to the rigorous standards applied to conventional drugs."

Nevertheless, a handful of doctors navigated the new regulatory hurdle and continued to perform fecal transplants in clinical trials. So, when I called around about the possibility of treating my C. diff. with a fecal microbial transplant, a sensible doctor might have offered to refer me to one of those approved practitioners. Instead, everyone I talked to refused to even entertain the idea, seemingly out of disgust.

"Yuck, you don't want that. Just stay on the vancomycin," my first doctor told me. A second, a gastroenterologist, simply substituted "gross" for "yuck." A third, more tactful, expressed relief that FDA policy absolved him from having to offer the procedure.

As it turns out, such responses weren't out of the ordinary. "There is a clear discordance between physician beliefs about [fecal transplants] and patient willingness to accept [fecal transplants] as a treatment," wrote a team of U.S. and Canadian physicians, after surveying more than 100 physicians about their attitudes toward the procedure. On average, physician respondents rated all aspects of the procedure to be "at least somewhat unappealing," whereas patients had demonstrated a clear willingness to accept the C. diff. treatment.

Gastroenterologist Ciarán Kelly mused in a 2013 editorial that the unappealing aesthetics of fecal microbial transplantation might be one of the main reasons it hadn't become routine therapy for C. diff. infections. In 2012, Brandt wrote that prospective transplant recipients were being discouraged by the "intransient negativism" of physicians, who described the procedure as "quackery," "a joke," and "snake oil" - despite its track record in case series.

And so it happened that when my C. diff. roared back, worse than before, after the end of my 10-day vancomycin course, my doctor's response was to simply prescribe more vancomycin. With each subsequent treatment, however, my likelihood of recovery dropped dramatically. I started the ordeal with an approximately 70 percent chance of recovery. After months of failed antibiotic treatments, my chances had sunk below 10 percent.

My last trip to the emergency room was a grim formality. The C. diff. battle now raged beyond my colon.

"You may want to tell loved ones about your dire circumstances," my gastroenterologist said.It dawned on me that my doctor would sooner let me die than discuss a fecal transplant. That's when I decided to do the transplant myself.

This was in the dark ages of fecal microbial transplantation, before the procedure became ingrained in the American psyche. But there were a handful of websites that offered advice on do-it-yourself fecal transplants. Some were more questionable than others. One dubiously suggested using pet feces for the donor sample.

But even with an appropriate two-legged donor, the procedure would carry risks of infections and the possibility of other adverse outcomes. My friends cautioned me against "going rogue" with an "extreme," "unapproved" treatment. But to me, the gamble was worth taking.

A New England Journal of Medicine article offered some procedural clues. For instance, my ideal donor would have a microbiome that was untainted by antibiotics. That ruled out Esteban, who had recently been administered antibiotics during an eye surgery. Ultimately, I turned to my 11-year-old daughter.

She responded openly and inquisitively, asking more questions than any of my doctors had. "Is this like in Clash of Clans when you have no troops left in your clan castle and you need someone else to donate some?" she said, referring to a popular multi-player video game.

Yes, it's exactly like that.

She agreed to do it, and at around 10 pm on a Tuesday, Esteban collected the sample. He dropped it into a blender, added saline, blended it, strained it, and poured the concoction into an enema bottle, as I lay depleted on the floor. My gut drank up the infusion as if it were dying of thirst. My colon, after five months of near-constant spasms, recovered in one transformative instant. Overnight, I went from having 30 bowel movements a day to having one. For breakfast the next morning, I ate a quesadilla loaded with black beans, cheese, salsa, lettuce, and guacamole. I've had no recurrence of C. diff. since.

Within a month of my five-month ordeal, the FDA announced a "compassionate use" exception to the restriction on fecal transplants, which gave physicians more freedom to offer the procedure to C. diff. patients. Within a year, MIT opened the first public stool bank, and the Cleveland Clinic named fecal transplantation a "Medical Innovation of 2014." Today, the stigma around fecal transplants has mostly worn off. A recent doctor, upon hearing my story, joked with a colleague that I'd had a fecal transplant "before they were cool."

I am glad that patients now have wider access to this life-saving treatment. Still, I remain wary of doctors and policymakers who once withheld that access from me and thousands of others like me. Their irrational aversion to feces - the biological agent that we all produce -nearly killed me.Susan D'Agostino is in the MA in Science Writing program at Johns Hopkins University and is a Taylor/Blakeslee fellow of the Council for the Advancement of Science Writing.SOTT Comment: As off-putting as the procedure may sounds, fecal transplants may just be the miracle procedure to fight off the plague of antibiotic resistant bacteria like C. diff. That doctors are so resistant to the idea likely means more and more people will be trying it themselves, or under the care of an alternative practitioner that cares more about the health of the patient than what arbitrary decision the FDA has made.

Related:

- Home

- Forum

- Chat

- Donate

- What's New?

-

Site Links

-

Avalon Library

-

External Sites

- Solari Report | Catherine Austin Fitts

- The Wall Will Fall | Vanessa Beeley

- Unsafe Space | Keri Smith

- Giza Death Star | Joseph P. Farrell

- The Last American Vagabond

- Caitlin Johnstone

- John Pilger

- Voltaire Network

- Suspicious Observers

- Peak Prosperity | Chris Martenson

- Dark Journalist

- The Black Vault

- Global Research | Michael Chossudovsky

- Corbett Report

- Infowars

- Natural News

- Ice Age Farmer

- Dr. Joseph Mercola

- Childrens Health Defense

- Geoengineering Watch | Dane Wigington

- Truthstream Media

- Unlimited Hangout | Whitney Webb

- Wikileaks index

- Vaccine Impact

- Eva Bartlett (In Gaza blog)

- Scott Ritter

- Redacted (Natalie & Clayton Morris)

- Judging Freedom (Andrew Napolitano)

- Alexander Mercouris

- The Duran

- Simplicius The Thinker

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Bookmarks