Crannogs: Neolithic artificial islands in Scotland stump archeologists

Erin Blakemore National Geographic

Wed, 12 Jun 2019 19:54 UTC

A diver holds a Neolithic (ca. 3,500 B.C) Ustan vessel found near a crannog (artificial island) in Loch Arnish, Scotland. © C. Murray

When it comes to studying Neolithic Britain (4,000-2,500 B.C.), a bit of archaeological mystery is to be expected. Since Neolithic farmers existed long before written language made its way to the British Isles, the only records of their lives are the things they left behind. And while they did leave us a lot of monuments that took, well, monumental effort to build-think Stonehenge or the stone circles of Orkney-the cultural practices and deeper intentions behind these sites are largely unknown.

Now it looks like there may potentially be a whole new type of Neolithic monument for archaeologists to scratch their heads over: crannogs.

Artificial islands commonly known as crannogs dot hundreds of Scottish and Irish lakes and waterways. Until now, researchers thought most were built when people in the Iron Age (800-43 B.C.) created stone causeways and dwellings in the middle of bodies of water. But a new paper published today in the journal Antiquity suggests that at least some of Scotland's nearly 600 crannogs are much, much older-nearly three thousand years older-putting them firmly in the Neolithic era. What's more, the artifacts that help push back the date of the crannogs into the far deeper past may also point to a kind of behavior not previously suspected in this prehistoric period.

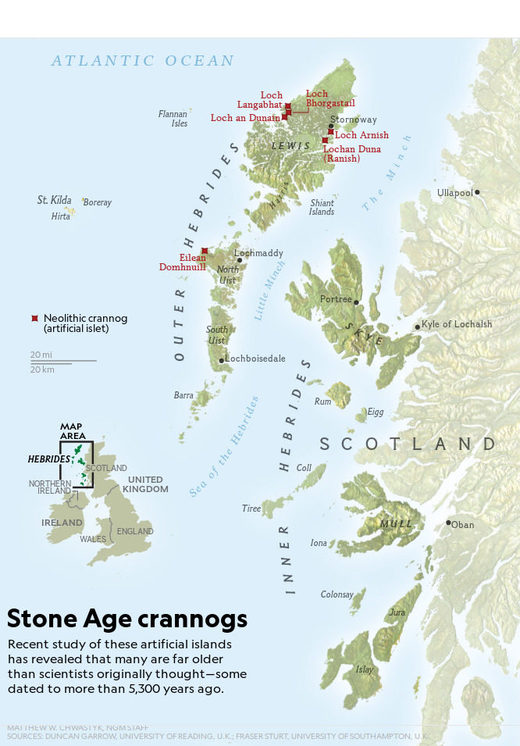

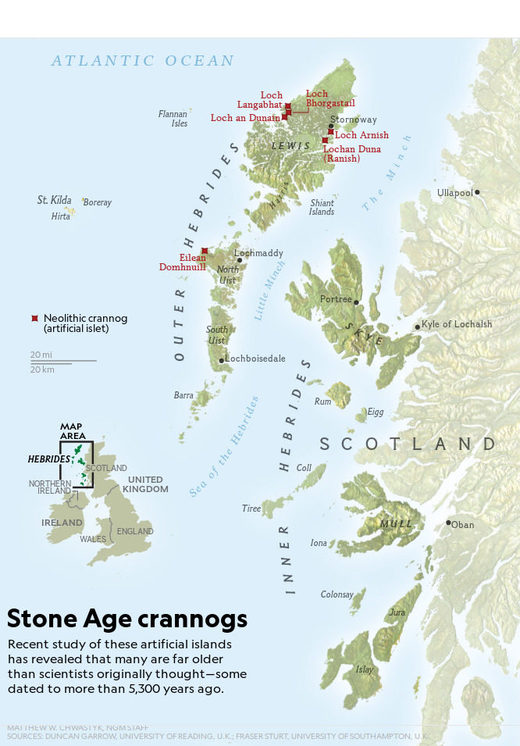

Recent study of these artificial islands has revealed that many are far older than scientists originally thought-some dated to more than 5,300 years ago.

© MATTHEW W. CHWASTYK, NGM STAFF SOURCES: DUNCAN GARROW, UNIVERSITY OF READING, U.K.; FRASER STURT, UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON, U.K.

A possibility that some crannogs may date as far back as the Neolithic first arose in the 1980s, when archaeologists excavating an Iron Age islet in a loch (lake) on Scotland's North Uist island realized they were looking at a Neolithic site instead. But though researchers suspected it wasn't the only case, searches of other crannogs in subsequent years yielded no evidence of Neolithic origins.

That changed in 2012, when a local diver found distinctively Neolithic pottery in the water around crannogs in the Outer Hebrides, the windswept islands off of Scotland's western mainland. Local museum officials and archaeologists joined in the search and eventually identified five artificially constructed islets with Neolithic origins, based on radiocarbon dating of stone-age pottery and/or ancient timbers discovered near the edges of the artificial structures.

Reuse of the islets over millennia made it hard to find signs of Neolithic life on the crannogs. But the water surrounding them tells a different story. For archaeologists used to finding just bits and pieces of six millennia-year-old pottery, the condition of the nearly intact Neolithic ceramic vessels found in the water around the crannogs is "amazing," says Duncan Garrow, an associate professor of archaeology at the University of Reading, who co-authored the paper. "I've never seen anything like it in British archaeology," he says. "People seem to have been chucking this stuff in the water."

But why were Neolithic people tossing their "good china" off of artificial islets? Without direct accounts from the time period, archaeologists can only speculate as to why the crannogs were built, how they were used, and why they became places for pottery disposal.

An aerial view of Scotland's stone-age artificial islands: 1) Arnish; 2) Bhorgastail; 3) Eilean Domhnuill (originally dated in the 1980s); 4) Lochan Duna; 5) Loch an Dunain; 6) Langabhat © Getmapping PLC

Garrow and his colleagues surmise they were used for feasting, another unknown set of religious or social rituals, or both. Vicki Cummings, an expert in Neolithic monuments from the University of Central Lancashire who was not involved in the research, says these crannogs appear isolated from both everyday Neolithic life (since they're located away from domestic settlements) and death (due to a lack of tombs or human remains).

Neolithic Britons loved building things with big rocks, but the crannogs are unlike settlements or other monuments. "Who would want to spend all of their time putting stones in a loch?" Cummings asks, pointing to the fact that some of the stones used to build crannogs weigh around 550 pounds. "It's a crazy thing to spend your time doing."

Cummings suggests the sites' isolation, and the pottery that surrounds them, could point to rituals that marked life transitions-like the passage from childhood to adulthood. "Clearly it was not appropriate to take the pottery [brought to the Neolithic crannogs] home," she says.

How many more of these "new" Neolithic monuments are out there? Only 20 percent of Scotland's nearly 600 crannogs have even been scientifically dated, and Cole Henley, a former archaeologist who specialized in Neolithic monuments and landscapes of the Outer Hebrides, warns against assuming that there are more of these sites, or that other places like Ireland may have them as well.

"Extrapolating is dangerous," he says. "It's like trying to do a jigsaw when you've only got five pieces and you've lost the box and don't know what the picture looks like."

Aerial views of the crannogs in Loch Bhorgastail (top) and Loch Langabhat (bottom).

© F. Sturt

Paper co-author Garrow admits the research is only just beginning, and his team plans to conduct a broader survey to date more crannogs in the Outer Hebrides. He hopes to use the scientific techniques that helped home in on the Neolithic crannogs-such as underwater surveys using side-scan sonar- to create even better ways of spotting new artificial stone-age islets, or prompt a reconsideration of sites already written off as Iron Age in origin. Still, it's unclear if the practice was widespread, and given the sheer volume of crannogs and the expense of surveying and archaeological diving, it's unlikely researchers will be able to date all of them any time soon.

But, says Cummings, that doesn't mean they're not out there. "Obviously we managed to miss these," she says. "[This new research] suggests that we really need to reconsider what we know."

It won't be easy. "We need to be open minded when we're looking for sites of this date," says Cummings. "They could be in any range of bizarre places." New Neolithic sites might be buried under what archaeologists always thought were Iron Age or medieval crannogs-or just hiding in plain sight in the center of a windswept Scottish loch.

--------------------------------------------

A 2016 report from the BBC provides more detail about the construction and possible uses of the crannogs:

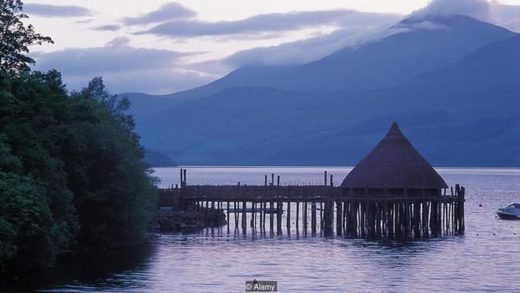

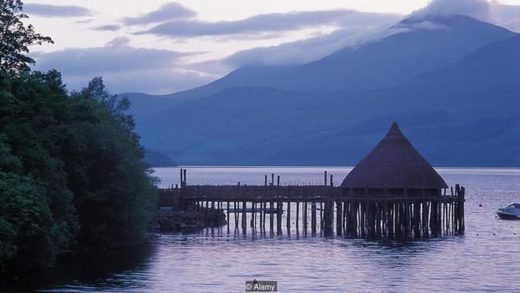

Barrie Andrian and Nick Dixon’s reconstruction of an ancient crannog was built without any metal, including bolts or nails © Alamy

Known as "crannogs" and build in lakes or lochs, some of these fortified islands date back as far as 5,000 years ago. Unlike similar constructions found in the European Alps - which were built on land that only flooded in later centuries - crannogs were always built to be artificial islands.

Supported by piles driven into the lake bed, some have several roundhouses on them. The more popularly recognised version is a single roundhouse on a platform. And they are unique to Scotland and Ireland. In Scotland, more than 350 have been confirmed, though the actual number could be far greater.

Despite the number of crannogs, archaeologists say that finding one can be like discovering a treasure chest. That is because, since most of these prehistoric dwellings are now completely underwater, they have often survived better than if they had been exposed on land - sometimes still retaining even the bracken that covered the floor. "It's very exciting," says Nick Dixon, director and founder of the Scottish Trust for Underwater Archaeology, who with Barrie Andrian leads the excavation of Oakbank crannog on Loch Tay in Kenmore, Scotland.

"You're lying on an Iron Age person's house floor after 2,500 years; there are bracken and ferns, still absolutely identifiable."

Started in 1980, the Oakbank dig was the first underwater excavation of a crannog in Scotland. Today, it is only about halfway through.

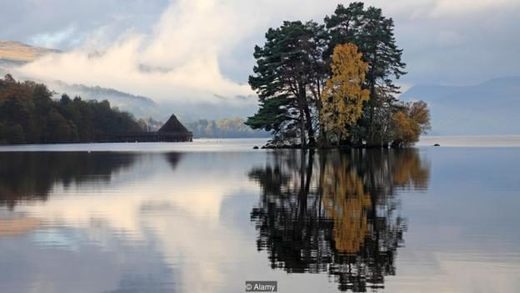

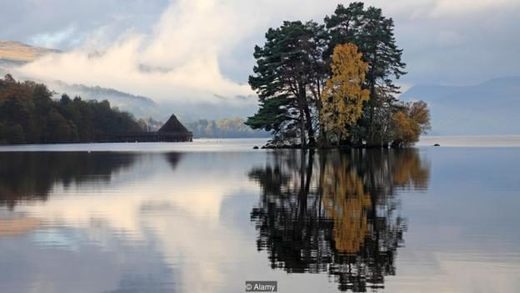

Loch Tay alone holds the remains of 18 known crannogs; the one shown here is a reconstruction at the Scottish Crannog Centre © Alamy

Oakbank is hardly alone. It is just one of 18 crannogs that have been surveyed in 13-mile-long Loch Tay alone. "Their construction recreates the original crannog as best they can"

But Loch Tay is not unusual. Beneath their surface, many of Scotland's lochs hide the remains of a dozen crannogs or more, most of them dating to the same eras - around either the 5th or 2nd Centuries BC.

The number of crannogs is remarkable because building a crannog is not an easy task. Dixon and Andrian know because they did it themselves, creating Scotland's only reconstructed prehistoric crannog at the Scottish Crannog Centre.

Set further down Loch Tay from their Oakbank excavation, their construction recreates the original crannog as best they can by drawing on findings they have made from the dig. Where they have not found evidence yet - for instance, for a roof - they have relied on outside sources and experimentation to see what works.

There is one key difference from the original: to make it accessible for visitors, there is a small bridge that leads to it from the shore. Other than that, Andrian and Dixon have tried to remain as true to its original structure as they can. "There is no metal in the entire recreated structure"

However, it is important to note, as researchers like Graeme Cavers of AOC Archaeology have pointed out, that even if it their reconstruction were completely accurate, it could only show a crannog as it was at a single point in history. Most crannogs, including Oakbank, were re-used off and on for the next 2,500 years. One example lies just across from the reconstructed crannog on Loch Tay: Priory Island, which was reused in the 12th Century as a priory and today is completely wooded.

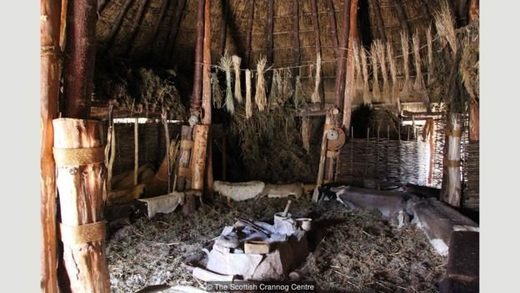

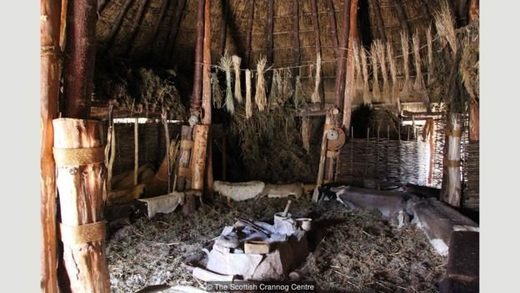

What is remarkable is how comfortable the crannog is.

While it looks small from the outside, inside it seems to open up. Andrian and Dixon estimate that some 20 or so people, likely an extended family, would have lived within a crannog of this size.

The roof is thatched. Bracken and ferns provide a prehistoric version of plush carpet. Furs are draped over low benches, and a hearth in the middle would have provided warmth and light.

There is no metal in the entire recreated structure, meaning no iron nails, screws, bolts or cables. Instead, everything is made from wood and organic materials.

Although the reconstructed crannog looks small from the outside, inside it seems to open up © The Scottish Crannog Centre

Because it is a pleasant day, the other benefit of the crannog is less immediately obvious: it is an ideal design for the Scottish climate. The conical roof is aerodynamic, and since the structure is made of timber, the whole settlement moves and flexes, a particularly important feature for an area that can see 100mph winds and pounding waves from the loch.

Building that kind of dwelling requires a high level of skill. It also needs abundant resources.

The reconstruction needed enough straight trees for 168 individual timber piles drilled into the loch bed, not to mention the entire structure above. "We learned pretty quickly that getting raw materials was an issue: where do you get lots of nice, straight trees? If you look around here, you see there are lots of nice straight trees - alder trees," Dixon says, gesturing to the thick forest that surrounds the loch.

"And that's exactly what people used. So we realised we had to cut these trees down in the winter, and start building in the springtime. If you ran out, you didn't want to go cutting trees in the summer. And this has been held up with evidence from other sites."

It is impossible to know just how long it would have taken these early settlers to build their crannogs. On the one hand, they were cutting down trees with bronze axes that blunted easily; on the other hand, they would have been honing their skills since they were children.

In some ways, it does not matter. "What you've got to remember is that their whole mindset is a million miles away from ours, mainly because they're not watching the clock; they're watching the seasons," Dixon says. "Nobody's coming and saying, 'Oh, it's 10 o'clock'. But it would have taken quite a long time."

Which leads to the main question: why did they go to all of this trouble in the first place?

Given the number and the diversity of crannogs, researchers say that there is no single answer. But because all crannogs are set off from land - often with a gate, or some kind of other barrier, at one end - most researchers are comfortable saying they were built to be defensive, even if they were rarely used for actual warfare.

The main giveaway that crannogs were not entirely meant for military use is their highly visible location. "Nobody's hiding away here," says Dixon.

"If you go 10 miles up the loch on the road, you can look down and see this on a sunny day. So no one's hiding. They're saying, 'We're the people that live here. Want to come and fight with us?'"

In that sense, the crannogs may be a little like the mysterious hill forts of Wales, which appeared around the same period. They were probably built partly to be a stronghold in case of attack but, equally, to look like they would be a stronghold in the case of attack. In other words, to impress everyone else.

Crannogs "represent a highly visible imprint on the landscape, clearly designed to look impregnable but also making a statement of presence," writes Cavers in his paper "Crannogs as buildings: The evolution of interpretation 1882-2011". And it is not just crannogs: "Through the later first millennium BC, domestic architecture became the principal investment of farming communities, standing in stark contrast to the monumental communal tombs and stone circles of earlier centuries."

But if this idea is true, it raises the question of why people began paying more attention to defence or status at this specific time.

Priory Island, the wooded island shown on the right, has was at least partly man-made by ancient people © Alamy

In Loch Tay, of the 13 crannogs that have been radio-carbon-dated, nine date back to the same period as Oakbank. Four others seem to have been built 2,400 and 1,800 years ago. Those two spikes in activity - one in the mid-first millennium BC, the second toward the end of the millennium - echo a trend seen throughout Scotland.

In part, this may have stemmed from the same reason that caused a boom in Welsh hill forts in the same period: climactic deterioration.

Around 536 BC, there was a well-documented catastrophe - likely caused by one if not two volcanic eruptions, or perhaps a series of comet impacts - that covered the Northern Hemisphere in a haze of dust. This caused crops to fail and made it colder and wetter. After another volcanic eruption around 210BC, when another dust veil appeared, the climate worsened again.

As researchers Mike Baillie and David Brown, among others, have pointed out, these events line up with a spike in building crannogs in both Ireland and Scotland.

Unlike the crannog at Loch Tay, this reconstructed settlement at the Craggaunowen Project in Ireland is an artificial island with several houses © Science Photo Library

"In an area like this, even a change of a few degrees means people have to move down from the higher lands," where cut rocks and stone circles point to earlier inhabitants, says Dixon. "With so many crannogs in the loch, there are so many answers that are just waiting to be discovered"

At Loch Tay alone, he adds, "We think around 500 people are moving down to the loch side. Because of pressure on land, people are being more defensive. And these crannogs are defensive settlements."

Andrian and Dixon are hoping that the continued excavation of Oakbank may provide a clearer picture. But, as the centre and excavation are entirely self-funded, they are limited in what they can do - particularly in terms of expanding to any of the other sites in the loch. "It's kind of frustrating that we're not able to get in, and do more, and train more people to get involved and carry on the research," Andrian says.

"With so many crannogs in the loch, there are so many answers that are just waiting to be discovered."

Related:

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Bookmarks