Although this may be a long article, it is quite comprehensive and rounds up the many facets scientists run into in practicing "Science":

Some of the biggest problems facing science

Julia Belluz, Brad Plumer, and Brian Resnick

Vox Wed, 07 Sep 2016 20:14 UTC

"Science, I had come to learn, is as political, competitive, and fierce a career as you can find, full of the temptation to find easy paths."

— Paul Kalanithi, neurosurgeon and writer (1977 - 2015)

Science is in big trouble. Or so we're told.

In the past several years, many scientists have become afflicted with a serious case of doubt — doubt in the very institution of science.

As reporters covering medicine, psychology, climate change, and other areas of research, we wanted to understand this epidemic of doubt. So we sent scientists a survey asking this simple question: If you could change one thing about how science works today, what would it be and why?

We heard back from 270 scientists all over the world, including graduate students, senior professors, laboratory heads, and Fields Medalists. They told us that, in a variety of ways, their careers are being hijacked by perverse incentives. The result is bad science.

The scientific process, in its ideal form, is elegant: Ask a question, set up an objective test, and get an answer. Repeat. Science is rarely practiced to that ideal. But Copernicus believed in that ideal. So did the rocket scientists behind the moon landing.

But nowadays, our respondents told us, the process is riddled with conflict. Scientists say they're forced to prioritize self-preservation over pursuing the best questions and uncovering meaningful truths.

"I feel torn between asking questions that I know will lead to statistical significance and asking questions that matter," says Kathryn Bradshaw, a 27-year-old graduate student of counseling at the University of North Dakota.

Today, scientists' success often isn't measured by the quality of their questions or the rigor of their methods. It's instead measured by how much grant money they win, the number of studies they publish, and how they spin their findings to appeal to the public.Scientists often learn more from studies that fail. But failed studies can mean career death. So instead, they're incentivized to generate positive results they can publish. And the phrase "publish or perish" hangs over nearly every decision. It's a nagging whisper, like a Jedi's path to the dark side."Is the point of research to make other professional academics happy, or is it to learn more about the world?"

—Noah Grand, former lecturer in sociology, UCLA

"Over time the most successful people will be those who can best exploit the system," Paul Smaldino, a cognitive science professor at University of California Merced, says.

To Smaldino, the selection pressures in science have favored less-than-ideal research: "As long as things like publication quantity, and publishing flashy results in fancy journals are incentivized, and people who can do that are rewarded ... they'll be successful, and pass on their successful methods to others."

Many scientists have had enough. They want to break this cycle of perverse incentives and rewards. They are going through a period of introspection, hopeful that the end result will yield stronger scientific institutions. In our survey and interviews, they offered a wide variety of ideas for improving the scientific process and bringing it closer to its ideal form.

Before we jump in, some caveats to keep in mind: Our survey was not a scientific poll. For one, the respondents disproportionately hailed from the biomedical and social sciences and English-speaking communities.

Many of the responses did, however, vividly illustrate the challenges and perverse incentives that scientists across fields face. And they are a valuable starting point for a deeper look at dysfunction in science today.

The place to begin is right where the perverse incentives first start to creep in: the money.

Academia has a huge money problem

To do most any kind of research, scientists need money:to run studies, to subsidize lab equipment, to pay their assistants and even their own salaries. Our respondents told us that getting — and sustaining — that funding is a perennial obstacle.

Their gripe isn't just with the quantity, which, in many fields, is shrinking. It's the way money is handed out that puts pressure on labs to publish a lot of papers, breeds conflicts of interest, and encourages scientists to overhype their work.

In the United States, academic researchers in the sciences generally cannot rely on university funding alone to pay for their salaries, assistants, and lab costs. Instead, they have to seek outside grants. "In many cases the expectations were and often still are that faculty should cover at least 75 percent of the salary on grants," writes John Chatham, a professor of medicine studying cardiovascular disease at University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Grants also usually expire after three or so years, which pushes scientists away from long-term projects. Yet as John Pooley, a neurobiology postdoc at the University of Bristol, points out, the biggest discoveries usually take decades to uncover and are unlikely to occur under short-term funding schemes.

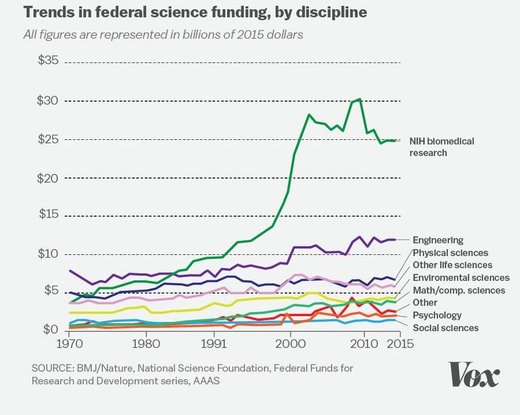

Outside grants are also in increasingly short supply. In the US, the largest source of funding is the federal government, and that pool of money has been plateauing for years, while young scientists enter the workforce at a faster rate than older scientists retire.

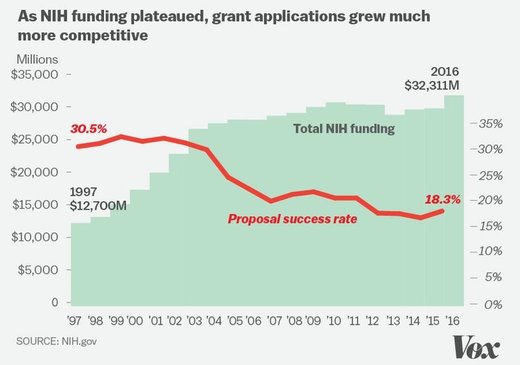

Take the National Institutes of Health, a major funding source. Its budget rose at a fast clip through the 1990s, stalled in the 2000s, and then dipped with sequestration budget cuts in 2013. All the while, rising costs for conducting science meant that each NIH dollar purchased less and less. Last year, Congress approved the biggest NIH spending hike in a decade. But it won't erase the shortfall.

The consequences are striking: In 2000, more than 30 percent of NIH grant applications got approved. Today, it's closer to 17 percent. "It's because of what's happened in the last 12 years that young scientists in particular are feeling such a squeeze," NIH Director Francis Collins said at the Milken Global Conference in May.

Some of our respondents said that this vicious competition for funds can influence their work. Funding "affects what we study, what we publish, the risks we (frequently don't) take," explains Gary Bennett a neuroscientist at Duke University. It "nudges us to emphasize safe, predictable (read: fundable) science."

Truly novel research takes longer to produce, and it doesn't always pay off. A National Bureau of Economic Research working paper found that, on the whole, truly unconventional papers tend to be less consistently cited in the literature. So scientists and funders increasingly shy away from them, preferring short-turnaround, safer papers. But everyone suffers from that: the NBER report found that novel papers also occasionally lead to big hits that inspire high-impact, follow-up studies.

"I think because you have to publish to keep your job and keep funding agencies happy, there are a lot of (mediocre) scientific papers out there ... with not much new science presented," writes Kaitlyn Suski, a chemistry and atmospheric science postdoc at Colorado State University.

Another worry: When independent, government, or university funding sources dry up, scientists may feel compelled to turn to industry or interest groups eager to generate studies to support their agendas.Already, much of nutrition science, for instance, is funded by the food industry — an inherent conflict of interest. And the vast majority of drug clinical trials are funded by drugmakers. Studies have found that private industry - funded research tends to yield conclusions that are more favorable to the sponsors."With funding from NIH, USDA, and foundations so limited ... researchers feel obligated — or willingly seek — food industry support. The frequent result? Conflicts of interest."

—Marion Nestle, food politics professor, New York University

Finally, all of this grant writing is a huge time suck, taking resources away from the actual scientific work. Tyler Josephson, an engineering graduate student at the University of Delaware, writes that many professors he knows spend 50 percent of their time writing grant proposals. "Imagine," he asks, "what they could do with more time to devote to teaching and research?"SOTT Comment: Additionally, some of the larger funds that are put towards research are often provided by the military industrial complex to fit their agenda, rather than research that would benefit humanity as a whole.

It's easy to see how these problems in funding kick off a vicious cycle. To be more competitive for grants, scientists have to have published work. To have published work, they need positive (i.e., statistically significant) results. That puts pressure on scientists to pick "safe" topics that will yield a publishable conclusion — or, worse, may bias their research toward significant results.

"When funding and pay structures are stacked against academic scientists," writes Alison Bernstein, a neuroscience postdoc at Emory University, "these problems are all exacerbated."

Fixes for science's funding woes

Right now there are arguably too many researchers chasing too few grants. Or, as a 2014 piece in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences put it: "The current system is in perpetual disequilibrium, because it will inevitably generate an ever-increasing supply of scientists vying for a finite set of research resources and employment opportunities."

"As it stands, too much of the research funding is going to too few of the researchers," writes Gordon Pennycook, a PhD candidate in cognitive psychology at the University of Waterloo. "This creates a culture that rewards fast, sexy (and probably wrong) results."

One straightforward way to ameliorate these problems would be for governments to simply increase the amount of money available for science. (Or, more controversially, decrease the number of PhDs, but we'll get to that later.) If Congress boosted funding for the NIH and National Science Foundation, that would take some of the competitive pressure off researchers.

But that only goes so far. Funding will always be finite, and researchers will never get blank checks to fund the risky science projects of their dreams. So other reforms will also prove necessary.

One suggestion: Bring more stability and predictability into the funding process. "The NIH and NSF budgets are subject to changing congressional whims that make it impossible for agencies (and researchers) to make long term plans and commitments," M. Paul Murphy, a neurobiology professor at the University of Kentucky, writes. "The obvious solution is to simply make [scientific funding] a stable program, with an annual rate of increase tied in some manner to inflation."Another idea would be to change how grants are awarded: Foundations and agencies could fund specific people and labs for a period of time rather than individual project proposals. (The Howard Hughes Medical Institute already does this.) A system like this would give scientists greater freedom to take risks with their work."Bitter competition leads to group leaders working desperately to get any money just to avoid closing their labs, submitting more proposals, overwhelming the grant system further. It's all kinds of vicious circles on top of each other."

—Maximilian Press, graduate student in genome science, University of Washington

Alternatively, researchers in the journal mBio recently called for a lottery-style system. Proposals would be measured on their merits, but then a computer would randomly choose which get funded.

"Although we recognize that some scientists will cringe at the thought of allocating funds by lottery," the authors of the mBio piece write, "the available evidence suggests that the system is already in essence a lottery without the benefits of being random." Pure randomness would at least reduce some of the perverse incentives at play in jockeying for money.

There are also some ideas out there to minimize conflicts of interest from industry funding. Recently, in PLOS Medicine, Stanford epidemiologist John Ioannidis suggested that pharmaceutical companies ought to pool the money they use to fund drug research, to be allocated to scientists who then have no exchange with industry during study design and execution. This way, scientists could still get funding for work crucial for drug approvals — but without the pressures that can skew results.

These solutions are by no means complete, and they may not make sense for every scientific discipline. The daily incentives facing biomedical scientists to bring new drugs to market are different from the incentives facing geologists trying to map out new rock layers. But based on our survey, funding appears to be at the root of many of the problems facing scientists, and it's one that deserves more careful discussion.

Too many studies are poorly designed. Blame bad incentives.

Scientists are ultimately judged by the research they publish. And the pressure to publish pushes scientists to come up with splashy results, of the sort that get them into prestigious journals. "Exciting, novel results are more publishable than other kinds," says Brian Nosek, who co-founded the Center for Open Science at the University of Virginia.

The problem here is that truly groundbreaking findings simply don't occur very often, which means scientists face pressure to game their studies so they turn out to be a little more "revolutionary." (Caveat: Many of the respondents who focused on this particular issue hailed from the biomedical and social sciences.)

Some of this bias can creep into decisions that are made early on: choosing whether or not to randomize participants, including a control group for comparison, or controlling for certain confounding factors but not others. (Read more on study design particulars here.)

Many of our survey respondents noted that perverse incentives can also push scientists to cut corners in how they analyze their data.

"I have incredible amounts of stress that maybe once I finish analyzing the data, it will not look significant enough for me to defend," writes Jess Kautz, a PhD student at the University of Arizona. "And if I get back mediocre results, there's going to be incredible pressure to present it as a good result so they can get me out the door. At this moment, with all this in my mind, it is making me wonder whether I could give an intellectually honest assessment of my own work."Increasingly, meta-researchers (who conduct research on research) are realizing that scientists often do find little ways to hype up their own results — and they're not always doing it consciously. Among the most famous examples is a technique called "p-hacking," in which researchers test their data against many hypotheses and only report those that have statistically significant results."Novel information trumps stronger evidence which sets the parameters for working scientists."

—Jon-Patrick Allem, postdoctoral social scientist, USC Keck School of Medicine

In a recent study, which tracked the misuse of p-values in biomedical journals, meta-researchers found "an epidemic" of statistical significance: 96 percent of the papers that included a p-value in their abstracts boasted statistically significant results.

That seems awfully suspicious. It suggests the biomedical community has been chasing statistical significance, potentially giving dubious results the appearance of validity through techniques like p-hacking — or simply suppressing important results that don't look significant enough. Fewer studies share effect sizes (which arguably gives a better indication of how meaningful a result might be) or discuss measures of uncertainty.

"The current system has done too much to reward results," says Joseph Hilgard, a postdoctoral research fellow at the Annenberg Public Policy Center. "This causes a conflict of interest: The scientist is in charge of evaluating the hypothesis, but the scientist also desperately wants the hypothesis to be true."

The consequences are staggering. An estimated $200 billion — or the equivalent of 85 percent of global spending on research — is routinely wasted on poorly designed and redundant studies, according to meta-researchers who have analyzed inefficiencies in research. We know that as much as 30 percent of the most influential original medical research papers later turn out to be wrong or exaggerated.

Fixes for poor study design

Our respondents suggested that the two key ways to encourage stronger study design — and discourage positive results chasing — would involve rethinking the rewards system and building more transparency into the research process.

"I would make rewards based on the rigor of the research methods, rather than the outcome of the research," writes Simine Vazire, a journal editor and a social psychology professor at UC Davis. "Grants, publications, jobs, awards, and even media coverage should be based more on how good the study design and methods were, rather than whether the result was significant or surprising."

Likewise, Cambridge mathematician Tim Gowers argues that researchers should get recognition for advancing science broadly through informal idea sharing — rather than only getting credit for what they publish.

"We've gotten used to working away in private and then producing a sort of polished document in the form of a journal article," Gowers said. "This tends to hide a lot of the thought process that went into making the discoveries. I'd like attitudes to change so people focus less on the race to be first to prove a particular theorem, or in science to make a particular discovery, and more on other ways of contributing to the furthering of the subject."

When it comes to published results, meanwhile, many of our respondents wanted to see more journals put a greater emphasis on rigorous methods and processes rather than splashy results."I think the one thing that would have the biggest impact is removing publication bias: judging papers by the quality of questions, quality of method, and soundness of analyses, but not on the results themselves," writes Michael Inzlicht, a University of Toronto psychology and neuroscience professor."Science is a human activity and is therefore prone to the same biases that infect almost every sphere of human decision-making."

—Jay Van Bavel, psychology professor, New York University

Some journals are already embracing this sort of research.PLOS One, for example, makes a point of accepting negative studies (in which a scientist conducts a careful experiment and finds nothing) for publication, as does the aptly named Journal of Negative Results in Biomedicine.

More transparency would also help, writes Daniel Simons, a professor of psychology at the University of Illinois. Here's one example: ClinicalTrials.gov, a site run by the NIH, allows researchers to register their study design and methods ahead of time and then publicly record their progress. That makes it more difficult for scientists to hide experiments that didn't produce the results they wanted. (The site now holds information for more than 180,000 studies in 180 countries.)

Similarly, the AllTrials campaign is pushing for every clinical trial (past, present, and future) around the world to be registered, with the full methods and results reported. Some drug companies and universities have created portals that allow researchers to access raw data from their trials.

The key is for this sort of transparency to become the norm rather than a laudable outlier.

Replicating results is crucial. But scientists rarely do it.

Replication is another foundational concept in science. Researchers take an older study that they want to test and then try to reproduce it to see if the findings hold up.

Testing, validating, retesting — it's all part of a slow and grinding process to arrive at some semblance of scientific truth. But this doesn't happen as often as it should, our respondents said. Scientists face few incentives to engage in the slog of replication. And even when they attempt to replicate a study, they often find they can't do so. Increasingly it's being called a "crisis of irreproducibility."

The stats bear this out: A 2015 study looked at 83 highly cited studies that claimed to feature effective psychiatric treatments. Only 16 had ever been successfully replicated. Another 16 were contradicted by follow-up attempts, and 11 were found to have substantially smaller effects the second time around. Meanwhile, nearly half of the studies (40) had never been subject to replication at all.

More recently, a landmark study published in the journal Science demonstrated that only a fraction of recent findings in top psychology journals could be replicated. This is happening in other fields too, says Ivan Oransky, one of the founders of the blog Retraction Watch, which tracks scientific retractions.

As for the underlying causes, our survey respondents pointed to a couple of problems. First, scientists have very few incentives to even try replication. Jon-Patrick Allem, a social scientist at the Keck School of Medicine of USC, noted that funding agencies prefer to support projects that find new information instead of confirming old results.

Journals are also reluctant to publish replication studies unless "they contradict earlier findings or conclusions," Allem writes.The result is to discourage scientists from checking each other's work. "Novel information trumps stronger evidence, which sets the parameters for working scientists."

The second problem is that many studies can be difficult to replicate. Sometimes their methods are too opaque. Sometimes the original studies had too few participants to produce a replicable answer. And sometimes, as we saw in the previous section, the study is simply poorly designed or outright wrong.

Again, this goes back to incentives: When researchers have to publish frequently and chase positive results, there's less time to conduct high-quality studies with well-articulated methods.

Fixes for under-replication

Scientists need more carrots to entice them to pursue replication in the first place. As it stands, researchers are encouraged to publish new and positive results and to allow negative results to linger in their laptops or file drawers.

This has plagued science with a problem called "publication bias" — not all studies that are conducted actually get published in journals, and the ones that do tend to have positive and dramatic conclusions.

If institutions started to reward tenure positions or make hires based on the quality of a researcher's body of work, instead of quantity, this might encourage more replication and discourage positive results chasing.

"The key that needs to change is performance review," writes Christopher Wynder, a former assistant professor at McMaster University. "It affects reproducibility because there is little value in confirming another lab's results and trying to publish the findings."The next step would be to make replication of studies easier. This could include more robust sharing of methods in published research papers. "It would be great to have stronger norms about being more detailed with the methods," says University of Virginia's Brian Nosek."Replication studies should be incentivized somehow, and journals should be incentivized to publish 'negative' studies. All results matter, not just the flashy, paradigm-shifting results."

—Stephanie Thurmond, biology graduate student, University of California Riverside

He also suggested more regularly adding supplements at the end of papers that get into the procedural nitty-gritty, to help anyone wanting to repeat an experiment. "If I can rapidly get up to speed, I have a much better chance of approximating the results," he said.

Nosek has detailed other potential fixes that might help with replication — all part of his work at the Center for Open Science.

A greater degree of transparency and data sharing would enable replications, said Stanford's John Ioannidis. Too often, anyone trying to replicate a study must chase down the original investigators for details about how the experiment was conducted.

"It is better to do this in an organized fashion with buy-in from all leading investigators in a scientific discipline," he explained, "rather than have to try to find the investigator in each case and ask him or her in detective-work fashion about details, data, and methods that are otherwise unavailable."

Researchers could also make use of new tools, such as open source software that tracks every version of a data set, so that they can share their data more easily and have transparency built into their workflow.

Some of our respondents suggested that scientists engage in replication prior to publication. "Before you put an exploratory idea out in the literature and have people take the time to read it, you owe it to the field to try to replicate your own findings," says JohnSakaluk, a social psychologist at the University of Victoria.

For example, he has argued, psychologists could conduct small experiments with a handful of participants to form ideas and generate hypotheses. But they would then need to conduct bigger experiments, with more participants, to replicate and confirm those hypotheses before releasing them into the world. "In doing so," Sakaluk says, "the rest of us can have more confidence that this is something we might want to [incorporate] into our own research."

Peer review is broken

Peer review is meant to weed out junk science before it reaches publication. Yet over and over again in our survey, respondents told us this process fails. It was one of the parts of the scientific machinery to elicit the most rage among the researchers we heard from.

Normally, peer review works like this: A researcher submits an article for publication in a journal. If the journal accepts the article for review, it's sent off to peers in the same field for constructive criticism and eventual publication — or rejection. (The level of anonymity varies; some journals have double-blind reviews, while others have moved to triple-blind review, where the authors, editors, and reviewers don't know who one another are.)

It sounds like a reasonable system. But numerous studies and systematic reviews have shown that peer review doesn't reliably prevent poor-quality science from being published.The process frequently fails to detect fraud or other problems with manuscripts, which isn't all that surprising when you consider researchers aren't paid or otherwise rewarded for the time they spend reviewing manuscripts. They do it out of a sense of duty — to contribute to their area of research and help advance science."I think peer review is, like democracy, bad, but better than anything else."

—Timothy Bates, psychology professor, University of Edinburgh

But this means it's not always easy to find the best people to peer-review manuscripts in their field, that harried researchers delay doing the work (leading to publication delays of up to two years), and that when they finally do sit down to peer-review an article they might be rushed and miss errors in studies.

"The issue is that most referees simply don't review papers carefully enough, which results in the publishing of incorrect papers, papers with gaps, and simply unreadable papers," says Joel Fish, an assistant professor of mathematics at the University of Massachusetts Boston. "This ends up being a large problem for younger researchers to enter the field, since that means they have to ask around to figure out which papers are solid and which are not."That's not to mention the problem of peer review bullying. Since the default in the process is that editors and peer reviewers know who the authors are (but authors don't know who the reviews are), biases against researchers or institutions can creep in, opening the opportunity for rude, rushed, and otherwise unhelpful comments. (Just check out the popular #SixWordPeerReview hashtag on Twitter)."Science is fluid; publishing isn't. It takes forever for research to make it to print, there is little benefit to try [to] replicate studies or publish insignificant results, and it is expensive to access the research."

—Amanda Caskenette, aquatic science biologist, Fisheries and Oceans Canada

These issues were not lost on our survey respondents, who said peer review amounts to a broken system, which punishes scientists and diminishes the quality of publications. They want to not only overhaul the peer review process but also change how it's conceptualized.

Fixes for peer review

On the question of editorial bias and transparency, our respondents were surprisingly divided. Several suggested that all journals should move toward double-blinded peer review, whereby reviewers can't see the names or affiliations of the person they're reviewing and publication authors don't know who reviewed them. The main goal here was to reduce bias.

"We know that scientists make biased decisions based on unconscious stereotyping," writes Pacific Northwest National University postdoc Timothy Duignan. "So rather than judging a paper by the gender, ethnicity, country, or institutional status of an author — which I believe happens a lot at the moment — it should be judged by its quality independent of those things."

Yet others thought that more transparency, rather than less, was the answer: "While we correctly advocate for the highest level of transparency in publishing, we still have most reviews that are blinded, and I cannot know who is reviewing me," writes Lamberto Manzoli, a professor of epidemiology and public health at the University of Chieti, in Italy. "Too many times we see very low quality reviews, and we cannot understand whether it is a problem of scarce knowledge or conflict of interest."Perhaps there is a middle ground. For example, eLife, a new open access journal that is rapidly rising in impact factor, runs a collaborative peer review process. Editors and peer reviewers work together on each submission to create a consolidated list of comments about a paper. The author can then reply to what the group saw as the most important issues, rather than facing the biases and whims of individual reviewers. (Oddly, this process is faster — eLife takes less time to accept papers than Nature or Cell.)"We need to recognize academic journals for what they are: shop windows for incomplete descriptions of research, that make semi-arbitrary editorial [judgments] about what to publish and often have harmful policies that restrict access to important post-publication critical appraisal of published research."

—Ben Goldacre, epidemiology researcher, physician, and author

Still, those are mostly incremental fixes. Other respondents argued that we might need to radically rethink the entire process of peer review from the ground up.

"The current peer review process embraces a concept that a paper is final," says Nosek. "The review process is [a form of] certification, and that a paper is done." But science doesn't work that way. Science is an evolving process, and truth is provisional. So, Nosek said, science must "move away from the embrace of definitiveness of publication."

Some respondents wanted to think of peer review as more of a continuous process, in which studies are repeatedly and transparently updated and republished as new feedback changes them — much like Wikipedia entries. This would require some sort of expert crowdsourcing.

"The scientific publishing field — particularly in the biological sciences — acts like there is no internet," says Lakshmi Jayashankar, a senior scientific reviewer with the federal government. "The paper peer review takes forever, and this hurts the scientists who are trying to put their results quickly into the public domain."

One possible model already exists in mathematics and physics, where there is a long tradition of "pre-printing" articles. Studies are posted on an open website called arXiv.org, often before being peer-reviewed and published in journals. There, the articles are sorted and commented on by a community of moderators, providing another chance to filter problems before they make it to peer review.

"Posting preprints would allow scientific crowdsourcing to increase the number of errors that are caught, since traditional peer-reviewers cannot be expected to be experts in every sub-discipline," writes Scott Hartman, a paleobiology PhD student at the University of Wisconsin.

And even after an article is published, researchers think the peer review process shouldn't stop. They want to see more "post-publication" peer review on the web, so that academics can critique and comment on articles after they've been published. Sites like PubPeer and F1000Research have already popped up to facilitate that kind of post-publication feedback.

"We do this a couple of times a year at conferences," writes Becky Clarkson, a geriatric medicine researcher at the University of Pittsburgh. "We could do this every day on the internet."

The bottom line is that traditional peer review has never worked as well as we imagine it to — and it's ripe for serious disruption.

Too much science is locked behind paywalls

After a study has been funded, conducted, and peer-reviewed, there's still the question of getting it out so that others can read and understand its results.

Over and over, our respondents expressed dissatisfaction with how scientific research gets disseminated. Too much is locked away in paywalled journals, difficult and costly to access, they said. Some respondents also criticized the publication process itself for being too slow, bogging down the pace of research.

On the access question, a number of scientists argued that academic research should be free for all to read. They chafed against the current model, in which for-profit publishers put journals behind pricey paywalls.

A single article in Science will set you back $30; a year-long subscription to Cell will cost $279. Elsevier publishes 2,000 journals that can cost up to $10,000 or $20,000 a year for a subscription.Many US institutions pay those journal fees for their employees, but not all scientists (or other curious readers) are so lucky. In a recent issue of Science, journalist John Bohannon described the plight of a PhD candidate at a top university in Iran. He calculated that the student would have to spend $1,000 a week just to read the papers he needed."My problem is one that many scientists have: It's overly simplistic to count up someone's papers as a measure of their worth."

—Lex Kravitz, investigator, neuroscience of obesity, National Institutes of Health

As Michael Eisen, a biologist at UC Berkeley and co-founder of the Public Library of Science (or PLOS), put it, scientific journals are trying to hold on to the profits of the print era in the age of the internet. Subscription prices have continued to climb, as a handful of big publishers (like Elsevier) have bought up more and more journals, creating mini knowledge fiefdoms.

"Large, publicly owned publishing companies make huge profits off of scientists by publishing our science and then selling it back to the university libraries at a massive profit (which primarily benefits stockholders)," Corina Logan, an animal behavior researcher at the University of Cambridge, noted. "It is not in the best interest of the society, the scientists, the public, or the research." (In 2014, Elsevier reported a profit margin of nearly 40 percent and revenues close to $3 billion.)

"It seems wrong to me that taxpayers pay for research at government labs and universities but do not usually have access to the results of these studies, since they are behind paywalls of peer-reviewed journals," added Melinda Simon, a postdoc microfluidics researcher at Lawrence Livermore National Lab.

Fixes for closed science

Many of our respondents urged their peers to publish in open access journals (along the lines of PeerJ or PLOS Biology). But there's an inherent tension here. Career advancement can often depend on publishing in the most prestigious journals, like Science or Nature, which still have paywalls.

There's also the question of how best to finance a wholesale transition to open access. After all, journals can never be entirely free. Someone has to pay for the editorial staff, maintaining the website, and so on. Right now, open access journals typically charge fees to those submitting papers, putting the burden on scientists who are already struggling for funding.

One radical step would be to abolish for-profit publishers altogether and move toward a nonprofit model. "For journals I could imagine that scientific associations run those themselves," suggested Johannes Breuer, a postdoctoral researcher in media psychology at the University of Cologne. "If they go for online only, the costs for web hosting, copy-editing, and advertising (if needed) can be easily paid out of membership fees."

As a model, Cambridge's Tim Gowers has launched an online mathematics journal called Discrete Analysis. The nonprofit venture is owned and published by a team of scholars, it has no publisher middlemen, and access will be completely free for all.Until wholesale reform happens, however, many scientists are going a much simpler route: illegally pirating papers."I personally spend a lot of time writing scientific Wikipedia articles because I believe that advances the cause of science far more than my professional academic articles."

—Ted Sanders, magnetic materials PhD student, Stanford University

Bohannon reported that millions of researchers around the world now use Sci-Hub, a site set up by Alexandra Elbakyan, a Russia-based neuroscientist, that illegally hosts more than 50 million academic papers. "As a devout pirate," Elbakyan told us, "I think that copyright should be abolished."

One respondent had an even more radical suggestion: that we abolish the existing peer-reviewed journal system altogether and simply publish everything online as soon as it's done.

"Research should be made available online immediately, and be judged by peers online rather than having to go through the whole formatting, submitting, reviewing, rewriting, reformatting, resubmitting, etc etc etc that can takes years," writes Bruno Dagnino, formerly of the Netherlands Institute for Neuroscience. "One format, one platform. Judge by the whole community, with no delays."

A few scientists have been taking steps in this direction. Rachel Harding, a genetic researcher at the University of Toronto, has set up a website called Lab Scribbles, where she publishes her lab notes on the structure of huntingtin proteins in real time, posting data as well as summaries of her breakthroughs and failures. The idea is to help share information with other researchers working on similar issues, so that labs can avoid needless overlap and learn from each other's mistakes.

Not everyone might agree with approaches this radical; critics worry that too much sharing might encourage scientific free riding. Still, the common theme in our survey was transparency. Science is currently too opaque, research too difficult to share. That needs to change.

Science is poorly communicated to the public

"If I could change one thing about science, I would change the way it is communicated to the public by scientists, by journalists, and by celebrities," writes Clare Malone, a postdoctoral researcher in a cancer genetics lab at Brigham and Women's Hospital.

She wasn't alone. Quite a few respondents in our survey expressed frustration at how science gets relayed to the public. They were distressed by the fact that so many laypeople hold on to completely unscientific ideas or have a crude view of how science works.

They griped that misinformed celebrities like Gwyneth Paltrow have an outsize influence over public perceptions about health and nutrition. (As the University of Alberta's Timothy Caulfield once told us, "It's incredible how much she is wrong about.")

They have a point. Science journalism is often full of exaggerated, conflicting, or outright misleading claims. If you ever want to see a perfect example of this, check out "Kill or Cure," a site where Paul Battley meticulously documents all the times the Daily Mail reported that various items — from antacids to yogurt — either cause cancer, prevent cancer, or sometimes do both.Sometimes bad stories are peddled by university press shops. In 2015, the University of Maryland issued a press release claiming that a single brand of chocolate milk could improve concussion recovery. It was an absurd case of science hype."Far too often, there are less than 10 people on this planet who can fully comprehend a single scientist's research."

—Michael Burel, PhD student, stem cell biology, New York University School of Medicine

Indeed, one review in BMJ found that one-third of university press releases contained either exaggerated claims of causation (when the study itself only suggested correlation), unwarranted implications about animal studies for people, or unfounded health advice.

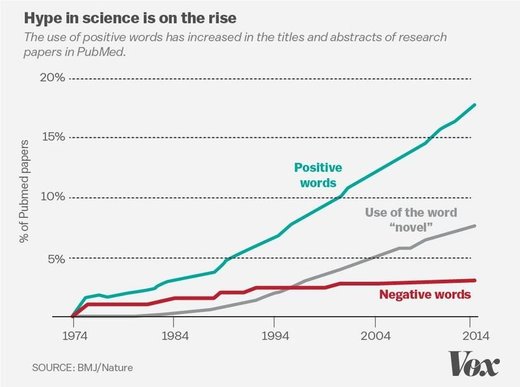

But not everyone blamed the media and publicists alone. Other respondents pointed out that scientists themselves often oversell their work, even if it's preliminary, because funding is competitive and everyone wants to portray their work as big and important and game-changing.

"You have this toxic dynamic where journalists and scientists enable each other in a way that massively inflates the certainty and generality of how scientific findings are communicated and the promises that are made to the public," writes Daniel Molden, an associate professor of psychology at Northwestern University. "When these findings prove to be less certain and the promises are not realized, this just further erodes the respect that scientists get and further fuels scientists desire for appreciation."

Fixes for better science communication

[...]

Full article: https://www.sott.net/article/329216-...facing-science

- Home

- Forum

- Chat

- Donate

- What's New?

-

Site Links

-

Avalon Library

-

External Sites

- Solari Report | Catherine Austin Fitts

- The Wall Will Fall | Vanessa Beeley

- Unsafe Space | Keri Smith

- Giza Death Star | Joseph P. Farrell

- The Last American Vagabond

- Caitlin Johnstone

- John Pilger

- Voltaire Network

- Suspicious Observers

- Peak Prosperity | Chris Martenson

- Dark Journalist

- The Black Vault

- Global Research | Michael Chossudovsky

- Corbett Report

- Infowars

- Natural News

- Ice Age Farmer

- Dr. Joseph Mercola

- Childrens Health Defense

- Geoengineering Watch | Dane Wigington

- Truthstream Media

- Unlimited Hangout | Whitney Webb

- Wikileaks index

- Vaccine Impact

- Eva Bartlett (In Gaza blog)

- Scott Ritter

- Redacted (Natalie & Clayton Morris)

- Judging Freedom (Andrew Napolitano)

- Alexander Mercouris

- The Duran

- Simplicius The Thinker

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Bookmarks