- Australian 🇦🇺 Scientists Discover 'Lost Atlantis?' or is it part of Lemuria, Mu

Australian scientists have discovered a lost 'Atlantis' continent 1.6 times the size of the UK. The vast landmass was apparently home to over half a million people. Priyanka Sharma brings you a report.

Lost 'Atlantis' Continent off Australia 🇦🇺 may have been home for half a million

Sonar mapping revealed signs of rivers and freshwater lakes across a now-sunken landscape almost twice the size of the UK, where humans could once have thrived.

- by Emma Bryce

Scientists have discovered a lost landmass off the coast of Australia that could have supported a population of up to half a million people.

About 70,000 years ago, a vast swathe of land that's now submerged off the coast of Australia could once have supported a population of half a million people. The undersea territory was so large it could have functioned as a stepping stone for migration from modern-day Indonesia to Australia 🇦🇺, finds a new study published Dec. 15 in the journal Quaternary Science Reviews.

"We're talking about a landscape that's quite submerged, over 100 meters [330 feet] below sea level today," Kasih Norman, an archeologist at Griffith University in Queensland, Australia, and lead author on the new study, told Live Science. This Australian "Atlantis" comprised a large stretch of continental shelf that, when above sea level, would have connected the regions of Kimberley and Arnhem Land, which today are separated by a large ocean bay.

This ancient expanded Australian landmass once formed part of a palaeocontinent that connected modern-day Australia, New Guinea, and Tasmania into a single unit known as Sahul.

The sunken continental shelf sits off the northern coast of Australia. (Image credit: Photography by Mangiwau/Getty Images)A habitable, populated landscape?

Despite its scale, until now there's been little research into whether humans could have inhabited the now-sunken shelf. "There's been an underlying assumption in Australia that our continental margins were probably unproductive and weren't really used by people, despite the fact that we have evidence from many parts of the world that people were definitely out on these continental shelves in the past," Norman said.

A huge supercontinent called Sahul connected the Australian 🇦🇺 mainland with New Guinea and Tasmania, as well as including the North West Shelf

Her new study turns that assumption on its head. It brings regional data on sea levels between 70,000 and 9,000 years ago, together with detailed maps of seafloor features from the submerged continental shelf, provided by sonar mapping from ships. This combination painted a picture of dramatically changing conditions on that shelf over the studied period.

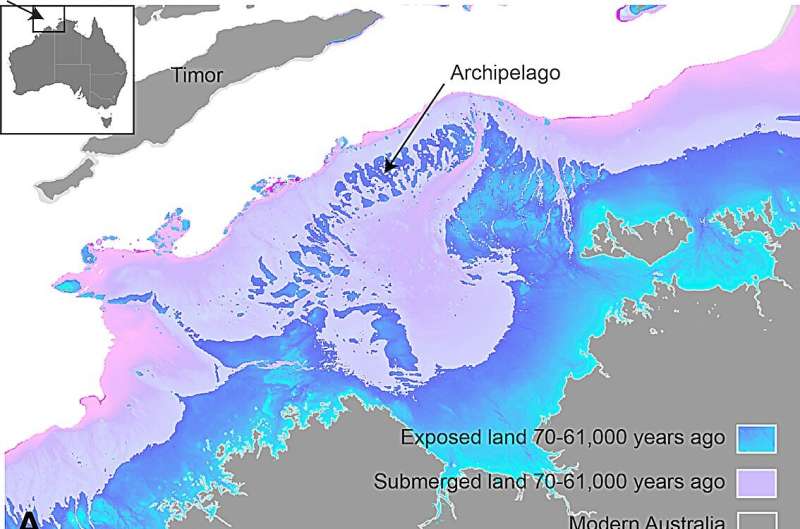

Firstly, the data showed that between 71,000 and 59,000 years ago, sea levels were roughly 130 feet (40 m) lower than they are today, a dip that exposed a curving necklace of islands at the Australian continent's outer northwestern edge. This archipelago lay within reaching distance, by voyaging boats, of the Southeast Asian island of Timor, which itself is not far from Indonesia.

Then, between 29,000 and 14,000 years ago, there was another more precipitous dip in sea levels, coinciding with the peak of the last ice age. This was a time when large amounts of water became suspended in ice, which further lowered sea levels.

These plummeting levels exposed a large swathe of continental shelf right beside modern-day Australia. "We're really looking at a landmass that was about 1.6 times the size of the UK," Norman said.

This, combined with the previously exposed ring of islands, "would have meant that there was basically a contiguous archipelago environment to move from the Indonesian archipelago, across to Sahul, and then from that archipelago into the supercontinent itself," Norman said. This could have enabled what she called a "staged migration" between modern-day Indonesia and Australia.

Meanwhile, the sonar mapping revealed a landscape where humans could well have thrived: a tall, sheltering escarpment, containing an inland sea adjacent to a large freshwater lake. There was also evidence of winding river beds carved across the land.

Norman calculated that the large shelf, with these life-supporting features, could have harbored anywhere between 50,000 and half a million people. "It's important to bear in mind these aren't real population numbers we're talking about, it's just a matter of projecting the carrying capacity of our landscape," she said. "We're basically saying it could have had that many people."

The shelf stretched all the way to the island of Timor.

Retreat and Migration

However, there are clues from other research that this once exposed plateau was indeed home to hundreds of thousands of people. Ironically, these come from a time when the potential inhabitants of this Atlantis would have been forced away by rising tides from their new found land.

As the last ice age began to taper off, melting ice caps shed water into a rising sea, Between roughly 14,000 and 14,500 years ago, sea level rose at an accelerating rate, going from about 3.2 feet (1m) per year to a meter [3.2 feet] over the course of 100 years, to 16 feet. "In this 400 year period, over 100,000 square kilometers of land go underwater," Norman said. Between 12,000 and 9,000 years ago, that pattern repeated, and another 100,000 square kilometers were swallowed up by the sea. "People would have really seen the landscape change in front of them, and been pushed back ahead of that encroaching coastline quite rapidly," Norman said.

This hypothesis is supported by other research. A recent study published in the journal Nature analyzed the genetics of people living in the Tiwi Islands, which sit on the edge of the shelf today. It revealed that at the end of the last glacial period, there was change in genetic signatures indicating an influx of new populations there. What's more, about 14,000 years ago, and then again between 12,000 and 9,000 years ago, the archaeological record at edge regions of modern-day Australia shows an increase in the deposit of stone tools — "which is normally interpreted to mean that there's a lot more people suddenly in that area," Norman said.

Around this time in Kimberly and Arnhem Land, cave art also changed to incorporate new styles and subjects, including more human figures in the mix. This may have been from new people arriving in the area, Norman said.

She hopes her research will motivate others to pay closer attention to the archeological importance of Australia's sunken continental shelf.

"It's quite fascinating to look at how people dynamically responded to events in the past and obviously survived them and thrived. I would hope that there might be something we can take from that, that we can apply to future climate change and sea level rise in the next few hundred years."

People once lived in a vast region in north-western Australia—and it had an inland sea

- source (with more pictures)

by Kasih Norman

Left: Satellite image of the submerged northwest shelf region. Right: Drowned landscape map of the study area.

For much of the 65,000 years of Australia's 🇦🇺 human history, the now-submerged northwest continental shelf connected the Kimberley and western Arnhem Land. This vast, habitable realm covered nearly 390,000 square kilometers, an area one-and-a-half times larger than New Zealand is today.

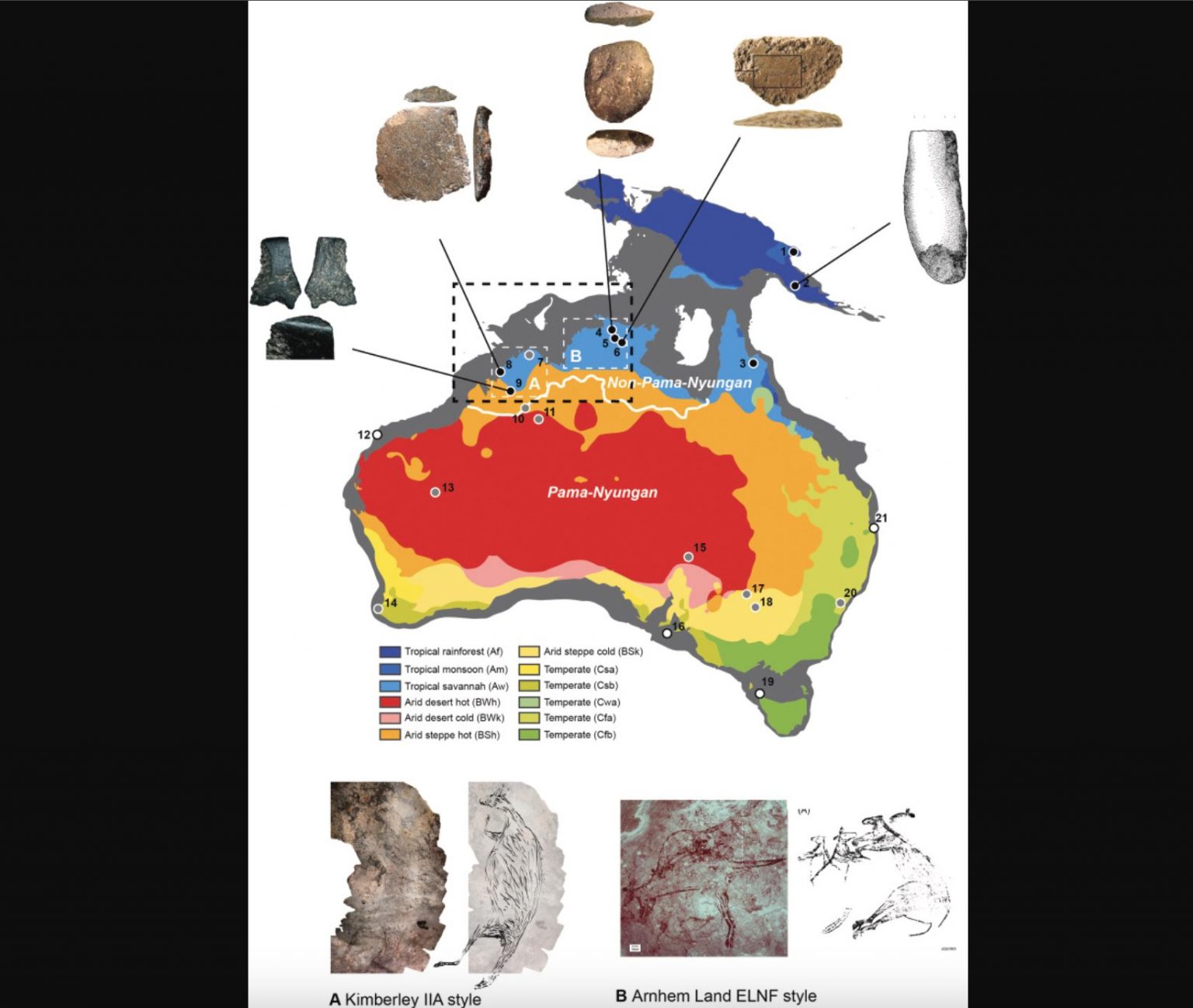

It was likely a single cultural zone, with similarities in ground stone-axe technology, styles of rock art, and languages found by archaeologists in the Kimberley and Arnhem Land.

There is plenty of archaeological evidence humans once lived on continental shelves—areas that are now submerged—all around the world. Such hard evidence has been retrieved from underwater sites in the North Sea, Baltic Sea and Mediterranean Sea, and along the coasts of North and South America, South Africa and Australia.

In a newly published study in Quaternary Science Reviews, we reveal details of the complex landscape that existed on the Northwest Shelf of Australia. It was unlike any landscape found on our continent today.

Continental Split

Around 18,000 years ago, the last ice age ended. Subsequent warming caused sea levels to rise and drown huge areas of the world's continents. This process split the supercontinent of Sahul into New Guinea and Australia 🇦🇺, and cut Tasmania off from the mainland.

Unlike in the rest of the world, the now-drowned continental shelves of Australia were thought to be environmentally unproductive and little used by First Nations peoples.

But mounting archaeological evidence shows this assumption is incorrect. Many large islands off Australia's coast—islands that once formed part of the continental shelves—show signs of occupation before sea levels rose.

Stone tools have also recently been found on the sea floor off the coast of the Pilbara region of Western Australia.

However, archaeologists have only been able to speculate about the nature of the drowned landscapes people roamed before the end of the last ice age, and the size of their populations.

Our new research on the Northwest Shelf fills in some of those details. This area contained archipelagos, lakes, rivers and a large inland sea.

Mapping Ancient Landscape

To characterize how the Northwest Shelf landscapes changed through the last 65,000 years of human history, we projected past sea levels onto high-resolution maps of the ocean floor.

We found low sea levels exposed a vast archipelago of islands on the Northwest Shelf of Sahul, extending 500km towards the Indonesian island of Timor. The archipelago appeared between 70,000 and 61,000 years ago, and remained stable for around 9,000 years.

During lower sea levels, a vast archipelago formed on the Australian 🇦🇺 northwest continental shelf (top). A modern day example of an archipelago on a submerged continental shelf is the Åland Islands near Finland (bottom). Credit: US Geological Survey, Geoscience Australia

Thanks to the rich ecosystems of these islands, people may have migrated in stages from Indonesia to Australia, using the archipelago as stepping stones.

With descent into the last ice age, polar ice caps grew and sea levels dropped by up to 120 meters. This fully exposed the shelf for the first time in 100,000 years.

The region contained a mosaic of habitable fresh and saltwater environments. The most salient of these features was the Malita inland sea.

Our projections show it existed for 10,000 years (27,000 to 17,000 years ago), with a surface area greater than 18,000 square kilometers. The closest example in the world today is the Sea of Marmara in Turkey.

We found the Northwest Shelf also contained a large lake during the last ice age, only 30km north of the modern day Kimberley coastline. At its maximum extent it would have been half the size of Kati Thandi (Lake Eyre). Many ancient river channels are still visible on the ocean floor maps. These would have flowed into Malita sea and the lake.

Thriving Population

A previous study suggested the population of Sahul could have grown to millions of people.

Our ecological modeling reveals the now-drowned Northwest Shelf could have supported between 50,000 and 500,000 people at various times over the last 65,000 years. The population would have peaked at the height of the last ice age about 20,000 years ago, when the entire shelf was dry land.

This finding is supported by new genetic research indicating large populations at this time, based on data from people living in the Tiwi Islands just to the east of the Northwest Shelf.

At the end of the last ice age, rising sea levels drowned the shelf, compelling people to fall back as waters encroached on once-productive landscapes.

Retreating populations would have been forced together as available land shrank. New rock art styles appeared at this time in both the Kimberley and Arnhem Land.

Rising sea levels and the drowning of the landscape is also recorded in the oral histories of First Nations people from all around the coastal margin, thought to have been passed down for over 10,000 years.

This latest revelation of the complex and intricate dynamics of First Nations people responding to rapidly changing climates lends growing weight to the call for more Indigenous-led environmental management in this country and elsewhere.

As we face an uncertain future together, deep-time Indigenous knowledge and experience will be essential for successful adaptation.

Finding Argoland: how a lost continent resurfaced. Reconstruction and subsequent drift:

- Home

- Forum

- Chat

- Donate

- What's New?

-

Site Links

-

Avalon Library

-

External Sites

- Solari Report | Catherine Austin Fitts

- The Wall Will Fall | Vanessa Beeley

- Unsafe Space | Keri Smith

- Giza Death Star | Joseph P. Farrell

- The Last American Vagabond

- Caitlin Johnstone

- John Pilger

- Voltaire Network

- Suspicious Observers

- Peak Prosperity | Chris Martenson

- Dark Journalist

- The Black Vault

- Global Research | Michael Chossudovsky

- Corbett Report

- Infowars

- Natural News

- Ice Age Farmer

- Dr. Joseph Mercola

- Childrens Health Defense

- Geoengineering Watch | Dane Wigington

- Truthstream Media

- Unlimited Hangout | Whitney Webb

- Wikileaks index

- Vaccine Impact

- Eva Bartlett (In Gaza blog)

- Scott Ritter

- Redacted (Natalie & Clayton Morris)

- Judging Freedom (Andrew Napolitano)

- Alexander Mercouris

- The Duran

- Simplicius The Thinker

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Bookmarks